Insight: How Covid-19 Pandemic Birthed The “Saudi Way” Nationalism

While global leaders faced backlash after Covid-19, Saudi Arabia’s successful containment strengthened domestic nationalism and trust in the state.

The Covid-19 pandemic led to an unprecedented wave of anti-incumbent election results around the world. Electorates punished governing parties and presidents by weakening their support or even voting them out of office. Examples range from US Presidents Trump and Biden to the British Tories, France’s Emmanuel Macron, Japan’s Liberal Democrats, Germany’s center-left coalition, and even to Narendra Modi’s BJP. Saudi Arabia does not operate elections that might produce a similar anti-incumbent shift. Yet, this overwhelming evidence of political challenges to governing political leaders raises the question of how far the pandemic and its contentious response policies have changed Saudi domestic politics, too.

This insight article argues that the pandemic did have an effect on Saudi politics, yet different from most comparative cases. The pandemic and the comparatively successful and effective Saudi policy response created a new collective nationalist confidence and increased trust in Saudi state capacity and MBS’ top-down style of governing. Due to the global nature of the pandemic, the Saudi success story was turned into a narrative of Saudi superiority over the perceived failures of toothless Western democracies and totalitarian Chinese (and Australian) zero Covid policies. For many Saudis, this was not a battle between democracies and autocracies – but the conviction that the Saudi system and its newly built state capacity under MBS beats any other political system. This created a blueprint to assess international affairs, where criticism of Western powers is seen as justified and grounded in empirical facts.

The Effective Saudi Response to Covid-19

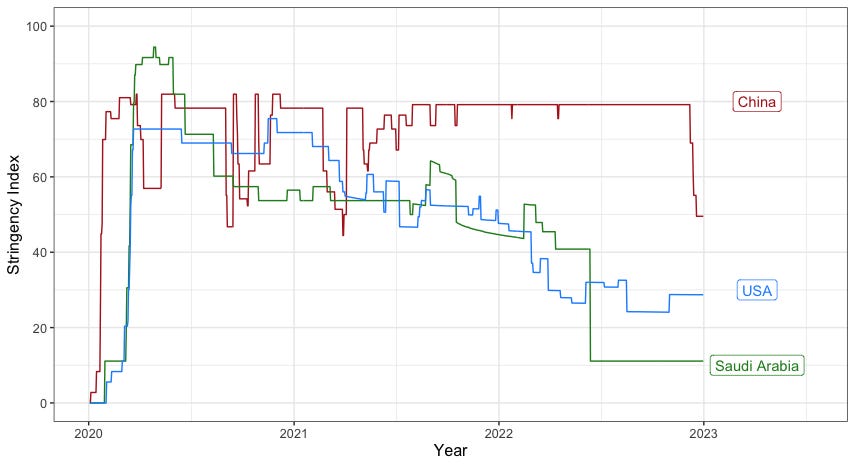

Saudi Arabia had implemented robust policies to curb the virus early on. The WHO confirmed that in Saudi Arabia “strong governance and intersectoral coordination have led to evidence-based decision making” and acknowledged that free COVID-19 services regardless of residency or citizenship status resulted in “equal access to services for everyone and minimized the impact of COVID-19 on migrants and other vulnerable groups.” The draconian measures included extensive limitations on both domestic and international travel, a socially distanced Hajj pilgrimage, lockdown and curfews. Corroborating both official claims and widespread public perceptions, Saudi Arabia’s policy response began more harshly than in many other countries. However, restrictions were then lifted gradually and steadily, avoiding the ‘ping-pong’ effect seen elsewhere—where premature easing of measures was repeatedly followed by renewed restrictions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Stringency Index for Measures to Curb the Pandemic for Select Countries. Note: The index is based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans, rescaled to a value from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest response). Source: WHO, downloaded via Our World in Data. Visuals created by the author and are taken from a publication in Perspectives on Politics (2024).

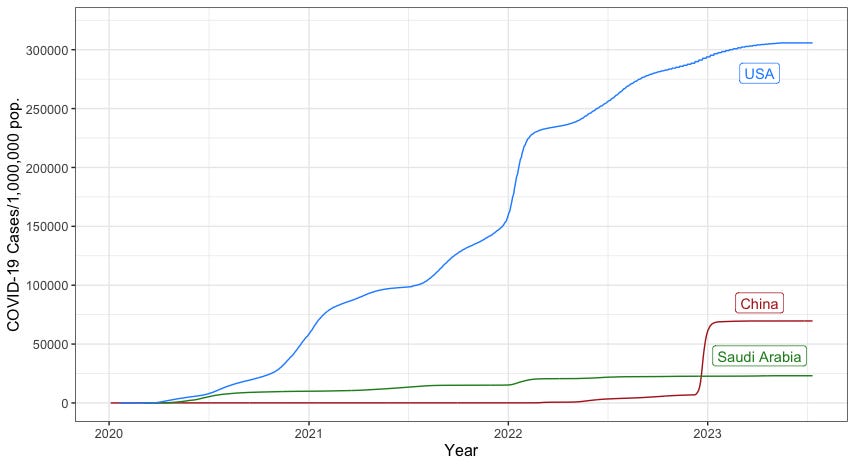

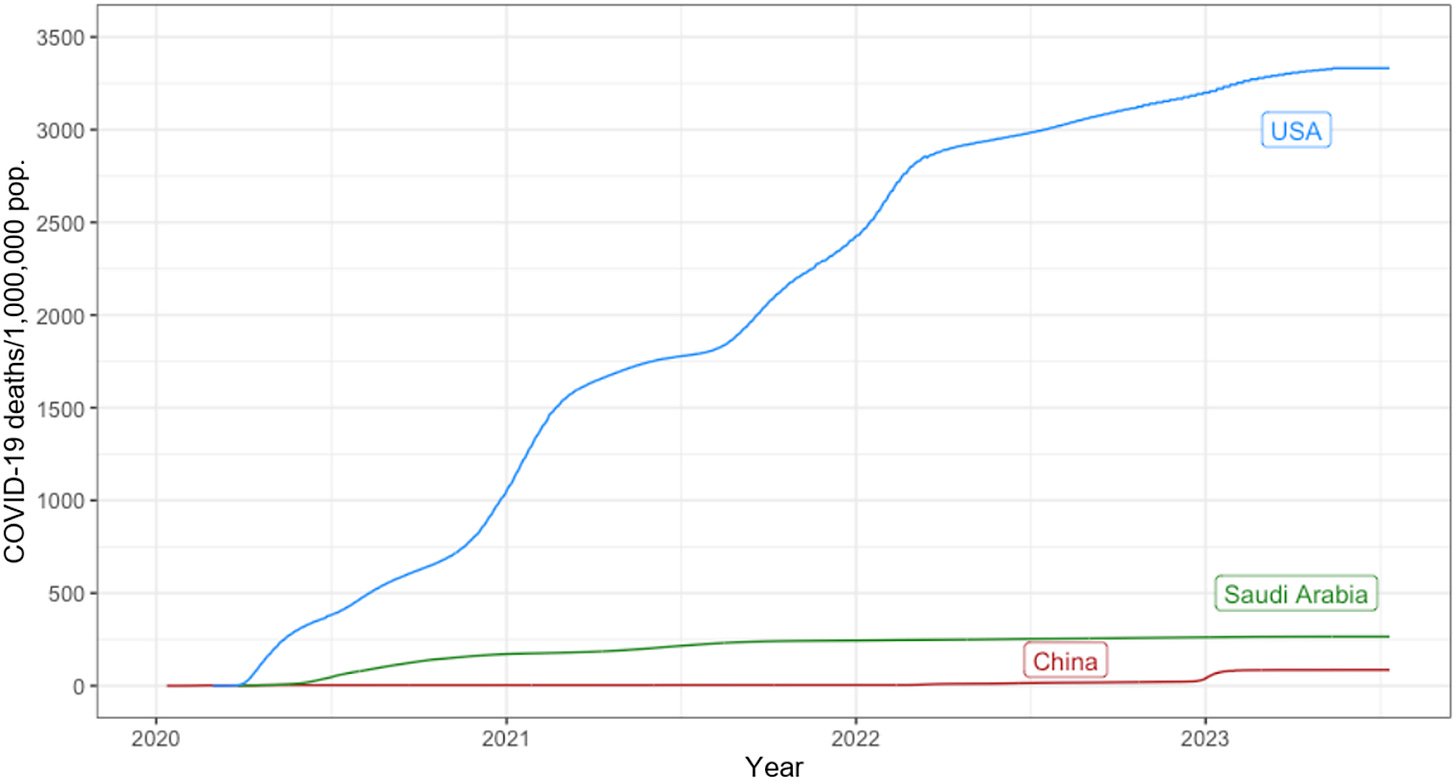

Indeed, there is evidence based on WHO data that the Saudi policy response was effective, leading to fewer cases and deaths than in other benchmark countries (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Cumulative Confirmed COVID-19 Cases for Selected Countries. Sources: See Figure 1.

Figure 3: Cumulative Confirmed COVID-19 Deaths for Select Countries. Sources: See Figure 1.

Covid-19 and the Birth of “Saudi Way” Nationalist Politics

These relatively effective measures and their fairly stringent implementation raise the question how they were justified politically. Over the course of the pandemic, the Saudi government and its relative independent intermediaries in the media developed a more robust narrative. While the Saudi government largely limited its communication strategy to explaining the Saudi approach and contributions to global public health, Saudi commentators in newspapers and on Twitter spun out these talking points. The commentators championed a cautious balancing act in the beginning – between praise and criticism for both the US and China – yet attacked what they perceived as a toothless approach in Western democracies increasingly over time.

By summer 2020, commentators celebrated the “Saudi way” of the pandemic response, having avoided a meltdown of the healthcare system and a broadly unexpected state capacity and effectiveness. Importantly, it was not so much the Saudi government that drove a more assertive media campaign but the Saudi media commentators, effectively blaming other states to have failed the test of managing the pandemic.

This newly gained confidence was not limited to commentators and intermediaries. The Saudi public voiced the globally second largest increase in public trust in the provision of healthcare between October 2018 and 2020, jumping by 21 points to 67% (only second to China). One main reason for this optimistic uptick may have been the previously notoriously dysfunctional Saudi bureaucracy. And among Saudi political institutions, the Ministry of Health was seen as particularly inefficient, even branded as the “graveyard of ministers” by some commentators. Thus, the effective public health policies were a pleasant surprise for many Saudis, lending credibility to MBS’ claims to ramp up Saudi state capacity as part of the Vision 2030 reform program.

In Saudi newspapers and social media, this new confidence in Saudi state capacity was translated into a belief of superiority of the Saudi system, compared with Western democracies as well as other non-democratic polities such as China. Western democracies were seen as toothless polities prioritizing individual interest while China’s zero covid policy was framed as a totalitarian but eventually in-effective state overreach. The “Saudi way” was seen as the golden mean. Thus, the soft power of Western democracies and to some extent China in Saudi Arabia went down the drain while giving MBS’ top-down governing style quite some significant credit. Importantly, this new confidence was not limited to the pandemic but translated into a broader nationalist confidence in the “Saudi way” among at least some segments of Saudi society. For them, the Saudi response to the pandemic was a global exam that the Saudi government excelled in – it became a blueprint to assess current global affairs.

Two major political crises of the past years attest to this. First, subsequent to Russia’s unprovoked attack of Ukraine in 2022 and Western countries’ (desperate) calls for the world to unite against the aggressor, Saudi commentators built on the newly found nationalist confidence to rebuff these demands. Equally, the Saudi government caused a massive outbreak of nationalist celebrations on Twitter when they disregarded US President Biden’s request to increase oil production in the early phase of the war. The “Saudi way” that was born in the pandemic became the mid-wife to the “Saudi national interest” on the global stage. Second, the Gaza war since October 2023 reinforced a sense among at least some segments of the Saudi public that Western political leaders and publics assessed political realities with a double standard when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Arab world more broadly, further damaging Western soft power. At the same time, the strong Saudi state capacity was presented in contrast with militant groups like Hamas, failing to produce improved socio-economic conditions for Palestinians in Gaza.

To conclude, the pandemic response has fueled Saudi nationalism and justified in the eyes of many Saudis MBS’ top-down governing style, ramping up state capacity and effectiveness. Saudi Arabia thereby stands in notable contrast to the global surge in anti-incumbent politics around the world. The Saudi government seems to have earned substantial credit among wide segments of the Saudi population through performance legitimacy. It remains to be seen whether the government will invest this political capital effectively to avoid growing discontent over shiny prestige projects that are seen as wasteful while cost of living and labor market hardships are ever increasing.